Cases in Comparative Politics 5th Edition Chapter Summaries

Comparative politics is a subdiscipline of political science. The goal of political science is to promote the comparison of different political entities, and comparative politics is the study of domestic politics within states. It differs from the other subdiscipline of political science—international relations—which instead focuses on politics between states. Traditionally, it has been assumed that whereas comparative politics studies politics in contexts where there is an ordering principle (the sovereign state), international relations, instead, studies politics in contexts without such a principle (the international system). The first is interested in studying politics in stable domestic contexts, the second in studying politics in unstable, extradomestic contexts. The first has concerned itself with studying order (because it is guaranteed by the sovereignty of the state), the second with studying disorder (an outcome of the anarchy of the relations between states). Some have questioned whether such a distinction between these subdisciplines is still plausible at the beginning of the 21st century.

This article is divided into four parts, beginning with an analysis of the main methods of comparative politics. The second part discusses the main theories of comparative politics, and the third part identifies some of the issues of comparative politics investigated in the various regions of the world. The article concludes with a discussion of the future of comparative politics in a globalized world.

Outline

- Methods in Comparative Politics

- The Experimental Method

- The Statistical Method

- The Case Study Method

- The Comparative Method

- Conclusions

- Theories of Comparative Politics

- Rational Choice Institutionalism

- The Theoretical Apparatus

- Criticisms

- Historical Institutionalism

- The Theoretical Apparatus

- Criticisms

- Sociological Institutionalism

- The Return of Political Culture

- Criticisms

- Conclusion

- Rational Choice Institutionalism

- Issues of Comparative Politics

- Democracy and Supranational Developments

- Democratization and Consolidation

- Quality of Democracy and Development

- Democracy and Constitutionalization

- Democracy and Representation

- Comparative Policy Analysis

- The Future of Comparative Politics

- Globalization and Europeanization

- Toward an International Comparative Politics

- Conclusion

- References

Methods in Comparative Politics

Although comparative politics is defined primarily by the phenomena it researches, it is also characterized by the method employed in that research. One cannot engage in comparative analysis without a method for comparing; a method is necessary for testing empirical hypotheses about relations between variables in different cases. Such hypotheses concern the relations between the variables that are held to structure the political phenomenon one wishes to study, investigate, or interpret. In general, political research aims to understand the links between the dependent variable (the outcome of the process one wants to explain), the independent variable (the structure, the context, the cognitive frame within which this process unfolds), and the intervening variable (the factor that exerts an influence on that given process). As Hans Keman observed, the question to understand is which independent variables can account for the variation of the dependent variable across different political systems.

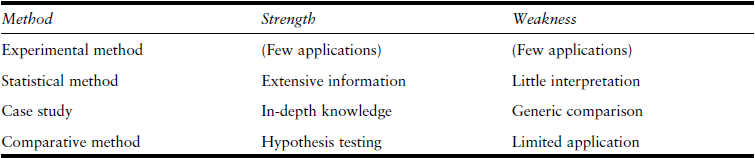

Political science employs several methods—four in particular—to check its research process and falsify its results: the experimental method, the statistical method, the case study, and the comparative method.

The Experimental Method

The experimental method can rarely be employed by political scientists. In contrast to the natural scientist, the political scientist cannot hope to study politics in a laboratory, in which the intervening factors can be kept constant so that the causal effects of the independent variable on the dependent variable can be reconstructed. Politics is rather more complex than what is studied in a science laboratory, above all because it involves factors that cannot be isolated and is structured by interactions that cannot be separated. Moreover, whereas in natural science the objects of study may be inanimate, the same cannot be said of politics and of those who engage in it. Politics is activated by actors (heads of governments, ministers, members of parliament, party leaders and activists, members of movements and associations, and citizens) who continually learn from their experience, thus modifying their behavior, even in the absence of variation in the independent variables.

The Statistical Method

The statistical method, however, is ever more widely employed by political scientists. It obviously presupposes the availability of numerical data. Those data are the product of a standardized process of quantitative measurement of aspects of political life—standardized because the same criteria of measurement can (and should) be used in different contexts. It goes without saying that, to be effective, this method requires a large number of quantitative and reliable data. However, whereas the experimental method presupposes the existence of a cause-and-effect relation, the statistical method does not. It provides information, but as such, it does not suggest an interpretation. Thus, without the support of a theory concerning relations between variables (measured quantitatively), the statistical method is destined to be of little use in scientific research. Moreover, when using this method, one is forced to neglect factors that are not easily quantifiable, such as cultural factors.

The Case Study Method

The analysis of the idiosyncratic factors mentioned above, instead, constitutes the object of the third method at the disposal of political research: the case study. This method has also characterized historical research and is designed to collect the largest possible amount of information (quantitative and qualitative) on a specific country (or other political entity). This method is also referred to as ideographic. A case study may have a purely descriptive purpose or, instead, may have an interpretative goal or even be designed to generate hypotheses (if not theories) susceptible to generalization (e.g., Alexis de Tocqueville's study of U.S. democracy, from which several hypotheses as well as a theory on the tendencies of Western democracies have been derived). This method is largely used in the United States, as is evident even from the comparative politics section of the book reviews in the American Political Science Association journal Perspectives on Politics, where there is an abundance of studies on single countries. This is not so (or rather less so) in Europe, where comparison generally involves the study of several cases.

The Comparative Method

There can be no doubt that the main method at the disposal of political science is the comparative method. In a now-classic 1970 essay, Giovanni Sartori pointed out that all political science presupposes, even if implicitly, a comparative frame of reference. The same author would write repeatedly that he who knows only one thing knows nothing at all. The comparative method requires, first, that the object to be compared be defined, next that the units used to compare and the time period to which the comparison refers be identified, and, finally, that the properties of those units be specified. Whereas the statistical method presupposes that the variables of many cases can be quantified, the comparative method is generally applied to a more limited number of cases. These cases may be very similar—that is, the strategy of the most similar research design—or they may be very dissimilar—the strategy of the most dissimilar research design. The first strategy allows more in-depth comparisons, whereas the second yields broader comparisons. The choice of strategy depends on the purpose of the study (see Table 1).

Table 1 Methods of Comparative Analysis

Comparative politics has become increasingly identified with the comparative method, to the extent that that method has become the defining characteristic of the academic discipline. It has permitted the construction of a particular type of scientific explanation based on correlations, as it assesses the validity of an explanation by assuming a correspondence between the properties of the independent variables and those of the dependent variables. But how and where do such correlations operate? The comparative method does not provide a clear answer. Regarding the how, the correlations operate if there are actors that activate them. How then should political agency be conceptualized? There is no univocal answer to this question. Regarding the where, the comparative method has to rely on few cases. The method of correlations has proved to be satisfactory when those cases are not only limited but also homogeneous (e.g., established democracies, post-Soviet democratizing countries). But if one wishes to broaden the perspective by comparing many nonhomogeneous cases (e.g., democracies, nondemocracies, and emerging democracies), what happens to a method based on correlations between uniform variables? It is no coincidence that political scientists have "regional" knowledge that cannot be easily applied in other "regions."

Conclusions

Certainly the buoyant growth of available data on the various political systems of the world has permitted complementing the statistical method with the comparative one, thus arriving at some classificatory systems that manage to comprise more cases belonging to different "regions," thereby making the analyses less Western centric. Yet the problem raised years ago by Sartori remains unsolved. Sartori argued that empirical concepts are subject to a sort of trade-off between their extension and their intensity. If a concept is applied to a large number of cases (extension), it will display only a limited ability to generate valid explanations for each case (intensity), and vice versa. When concepts are so abstract that they can be applied to the entire world, then, analytical vagueness is inevitable.

Comparison is a method used to test research hypotheses. The comparative method is generally employed by scholars of comparative politics, although it is increasingly complemented by the statistical method. The end of the Cold War in the early 1990s has brought about an enormous growth in the number of formally sovereign countries. Simultaneously, the available information resources (e.g., databases) also grew significantly, thus making it possible to have recourse to statistical comparisons. Yet a method is a tool at the disposal of researchers who take a scientific approach. It is a way of organizing the conceptual relations between the factors that are thought to structure the problem under investigation. Accordingly, there is a need for a theory that identifies those relations on the basis of a logically consistent argument. The theory informs us what to research and why. Bereft of a theoretical orientation, even the most sophisticated method provides only information or description. How to use or interpret the data depends on the theory.

Theories of Comparative Politics

There are many theories in comparative politics. The main theories generally have a focus on institutions; they are variations of the institutionalist approach. Institutionalism not only constitutes the main branch of the theories of comparative politics but also stands at the origin of political science as a whole. Without harking back to Aristotle, the genealogical tree of comparative politics had its roots at the beginning of the 20th century in the sociological constitutionalism of scholars such as Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto and the legal constitutionalism of scholars such as James Bryce and Woodrow Wilson. From there developed, after World War II, the comparative historical sociology of scholars such as Stein Rokkan and Harry Eckstein as well as the comparative political science of scholars such as Robert A. Dahl, Samuel P. Huntington, and Giovanni Sartori. These roots obviously have not prevented the subsequent emergence of noninstitutionalist developments, frequently deriving from political scientists' use of theoretical constructs from other social sciences. Examples include behavioralism (derived from social psychology), structural functionalism (derived from anthropology and subsequently from sociology), and systems theory (derived from the new cybernetic sciences).

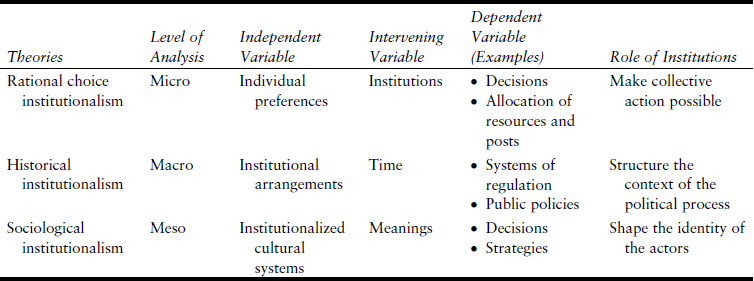

All these new developments had to live alongside the institutionalist approach (or "old" institutionalism), which never ceased to exert its influence on the comparative political research of the post–World War II period. Since the 1980s, the old institutionalism has been superseded by theoretical developments that have merged in the new institutionalism—new because it is distinct from its predecessor owing to its nonformalistic vision of institutions and norms. As noted by Ira Katznelson and Helen V. Milner, there are significant differences within the new or neoinstitutionalism. Some are microlevel institutionalist theories, as they take their point of departure from the preferences or interests of individual political actors or collective political actors understood as unitary. Others, instead, are macrolevel institutionalist theories, as they depart from supraindividual aggregates. Still others are mesolevel institutionalist theories, as they study the cognitive interactions between determined (but not limited) institutional configurations as well as the actors that operate within them. Whereas the macrolevel and mesolevel approaches treat the institutions (i.e., their structural characteristics or their cultural codes) as the independent variable, in the microlevel theories, this role is played instead by the preferences or the interests of the individual actors.

Rational Choice Institutionalism

The Theoretical Apparatus

The main microlevel theory of comparative politics is rational choice institutionalism. It constitutes an adaptation to political science of theories developed in the field of economics. The scholars who have most influenced the rational choice theorists are Anthony Downs, William Riker, Mancur Olson, and Douglass North. The point of reference for rational choice theorists is the neoclassical economic model, which conceptualizes collective action as the outcome of the behavior of individuals aiming to maximize their own utility (i.e., their own egoistic interests). Similarly, the political theory of rational choice postulates that the individuals who participate in politics are rational actors, acting on the basis of strategic considerations in order to maximize their utility. The actors' preferences are formed outside the political process. They are exogenous with respect to the interaction between the actors. Accordingly, individual preferences can be treated as the independent variable in this approach.

The basic unit of analysis of the rationalist theories is the actor. Politics is a game between individual actors or between collective actors understood as unitary subjects. As Riker has argued in many writings, the aim of this theory is to explain how collective action emerges in a multiactor game and to examine the microlevel foundations of processes that give rise to macrolevel effects. This does not imply that the macrolevel effects are necessarily rational (on the social level). Rather, as pointed out by Margaret Levi, a scholar working within this approach, collective action may be irrational even though individuals act in a rational way, unless they are subjected to the constraints of specific rules in the pursuit of their interests.

Institutions matter because they make collective action possible by lowering the transaction costs between the actors, by furnishing reliable information on the rules of the transaction itself, and by sanctioning free riding, thus making individual behavior predictable. Rational choice institutionalism assumes that institutions are necessary because they make possible virtuous interaction (i.e., cooperation) between the actors. Without the rules guaranteed and promoted by institutions, the game would become uncooperative. Institutional equilibrium obtains when none of the actors has an incentive to question the status quo because no actor is able to establish whether a more satisfactory equilibrium may result from doing so. Such equilibriums are defined as Pareto optimal, with reference to the well-known Italian economist and sociologist Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923). For rational choice theory, as it is employed in comparative politics, institutions and norms are intervening variables—factors that intervene from the outside to regulate the interactions between individual actors.

Rational choice institutionalism is a testable theory because, once the institutional framework that regulates behavior is known, it can yield falsifiable statements. It establishes a correlation of events identifying the causal mechanism that links the independent with the dependent variables. By assuming that individual behavior (as well as the behavior of collective actors whose actions are taken to be unitary), in any context whatsoever, is driven by the maximization of individual utility, rational choice theory is able to claim that its analytical framework has universal validity. Moreover, this scientific claim is supported by quantifying variables so that the rational choice theory can be expressed in a formal mathematical language. Indeed, according to these theorists, political science may legitimately compete with economics as long as it adopts the highly formalized analytical apparatus characteristic of the latter. Hence, rational choice theory derives its extraordinary academic and scientific success, especially among the community of U.S. political scientists, where it still sustains a strong hegemony of neoclassical economics within the social sciences.

Criticisms

Rational choice theory has not been spared criticism. First, it has been pointed out that an analysis that assumes institutions to be ahistorical entities ends up being overly abstract. Institutions are not aseptic rules but structures that are permeable to history. The same institutional structure may produce different effects in different historical periods. Second, it has also been shown that institutions constitute coherent and interconnected agglomerates of regulative structures. As a result, it is hardly plausible to examine a given institutional variable in isolation, assuming that the other institutional variables will remain constant. In reality, there is a reciprocal interaction between them, since the institutional variable considered may produce different effects if the variables with which it is linked are subjected to specific and unforeseen influences. Third, it has been argued that rational choice institutionalism runs the risk of turning into a remodeled functionalist theory, to the extent that it explains the existence of an institution with reference to the effects that it produces.

Fourth, it has been shown how an intentionalist conception of human agency lurks behind the theory of rational choice because it assumes that the process of creating an institution is intentional—that is, controlled by actors who correctly perceive the effects of the institutions created by them. Indeed, it is rarely the case that the actors intend to create institutions or that the actors correctly foresee the future impact of institutions. Moreover, rational choice institutionalists conceive the formation of institutions as a quasi-contractual process marked by voluntary agreements between relatively equal and independent actors, almost as if they still found themselves in a state of nature. Again, this is rarely the case. The elegance of the formal theory is insufficient to compensate for the weakness of the hypotheses of rational choice institutionalism concerning the driving forces of individual choice and the persistence of institutions.

Rational choice has been shown to be convincing in the analysis of microphenomena (e.g., why a certain decision was made in a committee of the U.S. Congress or why the negotiations within the intergovernmental conference of the European heads of state and government led to a certain outcome), but it is less successful in analyzing macrolevel processes (e.g., why the U.S. Congress has established itself as the most powerful legislature of the democratic world or why the process of European integration has given rise to a political system unforeseen by the states that had launched this process). Rational choice theory is generally of little use when the number of actors involved in the phenomenon under examination is large and when the timeframe is extended. It is certainly true that rational choice theory has positively contributed to raising the degree of formalization of political science. Yet as Barbara Geddes points out, it is equally beyond doubt that rational choice scholars have focused only on those phenomena that would allow such formalization. As a result, rational choice scholars have ended up studying a problem not because of its political relevance but of its ability to be formalized.

Historical Institutionalism

The Theoretical Apparatus

The main macrolevel theory of comparative politics is historical institutionalism. It has been developed by scholars such as Paul Pierson, Theda Skocpol, and Kathleen Thelen among others, elaborating the rich tradition of the historical social sciences of the 1950s and 1960s, represented by Barrington Moore Jr., Reinhard Bendix, and Seymour M. Lipset. It differs from rational choice institutionalism to the extent that it understands institutions not simply as arrangements that serve to regulate an interactive game but as historical structures that have origins and develop independently from those that operate within them. Moreover, whereas the analytical focus of rational choice institutionalism is on the actor, the analytical focus of historical institutionalism lies instead on institutional structures and their evolution over time.

Historical institutionalists analyze institutional and organizational configurations rather than single institutions in isolation, and they pay attention to processes of long duration. They show how general contexts and interactor processes give shape to the units that organize the political process. For them, time is a crucial intervening variable in explanations of specific outcomes. The aim of the analysis is to establish the sequences and the variations of scale and time that characterize a given political process. One of the fundamental concepts of historical institutionalism is path dependence. The theory of path dependence argues that, in politics, decisions made at time t will tend to shape the decisions made at time t 1. Once a given institution has asserted itself, it tends to reproduce over time. Contrary to what occurs in the economy, however, in politics, the marginal productivity of an institution increases over time, as Paul Pierson has shown.

To the individualistic outlook of rational choice theory, historical institutionalism has placed in opposition a vision of the political process as structured by institutions that have consolidated over time and thus shape this process. Also, windows of opportunity for institutional change open up under conditions of institutional crisis, but the actors, nevertheless, are constrained to act within the bounds inherited from the previous arrangements. Here, there is no heroic vision of actors as in the voluntaristic vision of agency that rational choice institutionalism assumes. Simultaneously, regarding historical macro-analyses, historical institutionalism has steered clear of the pitfalls of teleology that have frequently imprisoned historical research.

Criticisms

This theory too has been subject to criticism. First, historical institutionalism has paid less attention than rational choice institutionalism to the role of individual actors, and, in general, it has been more concerned with the possibility of agency in the historical evolution of a given institutional structure. The absence of a theory of agency has led historical institutionalists to emphasize the inertia of institutions (conceived as "sticky" structures), even though they were frequently constrained to modify or adapt themselves. For this reason, they are unable to provide precise indications concerning the chains of cause and effect that operate between the institutional macrostructures and the microlevel individual decisions. Second, historical institutionalism does not have at its disposal an analytical device to falsify its conclusions. Once a particular institution or policy has been reconstructed, it may prove difficult to imagine an alternative sequence. If every historical development is unique and if it is not possible to employ counterfactual hypotheses, then the possibility that the theory will fall into some kind of determinism is high.

Third, historical institutionalists have compared only a limited number of cases (and it could not have been otherwise, given their need to examine each case in depth), so how can valid knowledge be generated from these few cases unless supported by an extensive verification of the postulated hypotheses? It is no coincidence that the scholars who most extensively employ statistical methods criticize historical institutionalists for selecting their case studies according to the dependent variable that they wish to explain. As Gary King, Robert Keohane, and Sidney Verba have pointed out, historical institutionalism, like rational choice institutionalism, tends to select cases that fit with the approach adopted while ignoring those that do not. For example, historical institutionalists compare countries in which a political revolution occurred but do not explain why this did not happen in other countries with similar economic, social, and cultural characteristics.

Sociological Institutionalism

The Return of Political Culture

The main mesolevel theory of comparative politics is sociological institutionalism. Among the representatives of this approach, James G. March and Johan P. Olsen should be mentioned. According to sociological institutionalism, institutions are not just the source of rules for solving the problem of collective action or path-dependent structures that condition future decisions but configurations of meanings that the actors come to adopt. They solicit the formation of mental maps concerning the appropriate political behavior that guide the actors operating within institutions. They are sources of meaning independent of the actors that embrace them. Sociological institutionalism is a mesolevel theory that conceptualizes interactions between actors within institutional systems that are not limited (unlike limited systems, e.g., the committees of the U.S. Congress) and that are not extended (unlike systems such as welfare states).

Sociological institutionalism exhibits a strategic interest in culture (i.e., in meanings, symbols, common sense, ways of thinking, and cognitive frames). Indeed, it is a development of the rich tradition of cultural theory of comparative politics, which was rather relevant in political science until the 1970s. After a phase of decline, during the 1990s, the interest in political culture has clamorously returned to the stage of scientific debate. In particular, with the development of large-scale researches on social capital, the interest in political culture was and continues to be shared not only by political scientists but also by sociologists, economists, and anthropologists. Robert Putnam has been a pioneer in this regard, first conducting extensive empirical research on the relations between the social capital of the various regions of Italy and their institutional performance (Putnam, 1993) and then investigating the decline of social capital in the United States and its effects on the associationalism of that country (Putnam, 2000). In both cases, Putnam has shown how the quality of civic life forms the basis for the development of effective institutions in the context of a democratic society. This model was thus tested in a comparative research effort, directed by Putnam and published in 2002, which analyzed the relation between social capital and institutional performance in the main contemporary advanced democracies.

According to these theorists, political culture has to be treated as the independent variable and institutional performance as the dependent variable. Societies differ because they are characterized by different politico-cultural attitudes. Those cultural differences are relatively durable, even if they are not immutable. They can explain, for example, why some countries enjoy a stable democracy whereas others do not. The theorists of political culture have sought to provide an intersubjective analysis of politics, in which the intersubjectivity is conditioned (if not determined) by the cultural context in which it develops. This approach has been of considerable relevance for the contemporary world as it has provided an explanation of why institutional innovations encounter difficulties in unchanged cultural contexts and why processes of democratization find it difficult to advance in certain countries where the cultural assumptions of the previous regime have not been questioned. Yet, according to the critics, the concept of political culture risks being tautological in character. Citizens behave in a certain way because of the presence of a particular culture, but that particular culture is defined by the fact that citizens behave in a certain way. As a consequence, this concept makes it hard to explain the changes in social behavior and individual beliefs, changes that nevertheless occur regularly in contemporary political systems.

Sociological institutionalists have sought to come to terms with that debate by reducing the concept of political culture to the institutions that shape it and to the individuals that legitimate them. According to these scholars, institutions are not only rules of the game or crystallized historical arrangements but also encompass symbolic systems, cognitive maps, and moral frameworks of reference that represent the meanings that guide behavior. Accordingly, culture is transmitted by means of institutions, and because of this, they are simultaneously formative and constraining. Culture functions as the independent variable to the extent that it is institutionalized. Sociological institutionalism has undertaken a holistic analysis that seeks to recombine agency and structure in a comprehensive scheme of meanings and ways of thinking. As has been noted, anyone who has spent time waiting at a traffic light when nobody else was around will be able to understand the importance of internalized ways of thinking. In stable institutional contexts, as March and Olsen have noted, behavior is rarely motivated by the logic of utility but rather by the logic of appropriateness. Individuals behave in a certain way because that is what is expected of them in that particular institutional context. A given political culture is a component of the process that produces it, thus making the relation between the independent and the dependent variables in this process much more interactive.

Criticisms

Sociological institutionalism has not been immune to criticism. Two points are of particular relevance. First, as Peter A. Hall and Rosemary C. R. Taylor (1996) have argued, sociological institutionalism is based on the assumption of stable and legitimate institutional conditions. But what happens if one wants to explain the emergence or construction of new institutions? And what is the appropriate behavior in a situation of change? Processes of institution building inevitably tend to involve actors with diverse and contradictory cognitive frameworks and with conflicting interests. Second, the holistic approach of sociological institutionalism does not allow for a conceptualization, and even less measurement, of the contrasts between cognitive frameworks—that is, of competition or conflict between actors over how to understand and apply the predominant cultural frames. Institutions and actors stand in a relation of reciprocal influence: Whereas institutions contribute to defining the identity of the actors, sociological institutionalism must also hold that the characteristics of the latter (their decisions, their strategies, their visions) tend to define the identity of the former. Sociological institutionalism, thus, underestimates the impact of competition and conflict between actors (and between their contrasting interpretations of the appropriate behavior) on the definition of those same institutions. This implies that even consolidated institutions are cognitively less determined than sociological institutionalism assumes. For a summary of the discussion on the three institutionalisms, see Table 2.

Table 2 Neo-Institutionalist Theories

Conclusion

It is difficult to find a theory of comparative politics that does not refer, in one way or another, to institutions. For comparative politics scholars, institutions matter. Yet these theories differ significantly with respect to (a) what is understood to be an institution, (b) how institutions are created, (c) why and when they are important, and (d) how institutions change. The different viewpoints of institutionalist scholars have also highlighted the existence of different research programs. The rationalist approach is engaged in a formidable undertaking of simplification of comparative politics, as these scholars aim to provide their research program with a microeconomic foundation. Historical and sociological institutionalists, instead, seem to be engaged in an equally formidable enterprise of complexification of comparative politics, as they start from less limited and less restrictive assumptions. The former seek to construct a theory on the basis of the actor, whereas the latter start from the structures or the meanings embedded in them.

This division ultimately refers to the problem of what is to be understood as a theory in political science (Charles Ragin, 1994). According to the rationalists, political science needs to equip itself with an epistemological structure similar to that of the most formalized social science—namely, economics. For nonrational approaches, its social utility is justified by the ability to provide conceptual frameworks within which problems of public relevance can be examined but without any pretense of becoming a positive science. The first wants to predict what will happen; the other two want to explain what has happened. Which one of the available theories to employ should be decided by the problem under investigation and not as a matter of principle. Because it is the task of political science to investigate different problems, then, as Donatella Della Porta and Michael Keating submit, the lively theoretical pluralism of the discipline should be welcomed.

Issues of Comparative Politics

There are significant regional differences in the issues investigated by scholars in Africa, Asia, Latin America, Europe, and the United States since the end of the Cold War. However, those issues generally deal with the implications, functioning, and transformation of democracy. This is perhaps why institutional theories of comparative politics have become so successful. Democracy is a political regime that requires specific institutions, although those institutions may function properly if legitimated by coherent values (or political culture) diffused among the citizens. Since the end of the Cold War, democracy has become the only legitimate game in town. In 1900, only 10 countries were considered democracies, but in 1975, there were 30 such countries. In 2010, 115 out of 194 countries recognized by the United Nations were considered electoral democracies by the international nongovernmental organization Freedom House. This spectacular diffusion of democracy has inevitably attracted the interest of comparative politics scholars. Certainly, other topics unrelated to democracy have been investigated in a comparative perspective (e.g., revolutions, civil wars, ethnic strife, Islamic regimes). Nevertheless, the issues connected to democracy have represented the operational link between Western and non-Western scholars. The following sections identify a few areas of investigation within the vast literature.

Democracy and Supranational Developments

The debate on democratic models has continued to be at the center of comparative politics in the Western world. Thanks to the pioneering work of Arend Lijphart (1999), different patterns of democratic organization and functioning have been detected within the family of stable democratic countries. According to Lijphart, democracies might be classified according to the two ideal types—majoritarian democracies and consensual democracies—as a consequence of the structure of their social cleavages and institutional rules. This classification has been very important for freeing the analysis from the old normative argument, which assumed that there were more developed democracies (of course, the Anglo-American ones) and less developed democracies (of course, the continental European ones). Lijphart's classification has been revised by several authors. For some of them, such as Sergio Fabbrini (2008), the distinction between patterns of democracy concerns more their functional logic than their specific institutional properties. What matters is the fact that certain democracies function through an alternation in government of opposite political options, whereas others function through aggregation in government of all the main political options. Indeed, alternation in government takes place regularly in democracies that do not adopt a majoritarian (Westminster) first-past-the-post electoral system, such as Spain, Greece, or Germany. These democracies are competitive, notwithstanding their nonmajoritarian electoral systems. The consolidation of democracy in Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Asia has increased the number of countries to be considered for the identification of democratic patterns. In dealing with this process, Lijphart (in his subsequent works) has gradually (and surprisingly) shifted to a more normative approach, arguing that the consensual model represents a better model for the new democracies to adopt.

At the same time, the end of the Cold War and the prospect of the political reaggregation of the continent have accelerated the process of European integration; in the period from the Maastricht Treaty (1992) to the Lisbon Treaty (2009), Europe has become the European Union (or EU). The process of European integration was traditionally considered a unique experiment in international relations. International relations scholars were interested in explaining the process of integration rather than its outcome (i.e., the community system and its institutional characteristics). Since the Treaty of Maastricht (1992), a new generation of studies has started to investigate the EU as a political system. However, although the EU could no longer be considered an international regime, it could not be compared with other domestic political systems. In some cases, its supranational character has come to be considered exceptional, sui generis, unique by several observers and scholars. Or, if compared, the EU has been compared on the basis of generic or behavioral criteria, such as the style of decision making, ways in which political leaders interact, attitudes in managing public policies, and relations between interest groups. Lijphart (in his book of 1999) considered the EU as a case of consensual democracy.

A different comparative approach has been taken by other authors. Based on specific institutional criteria, Fabbrini (2010) has argued that the EU is a political system organized around multiple separations of powers. In the EU, there is no government as such, as in the parliamentary or semipresidential systems of its member states that are organized according to the principle of the fusion of powers. Contrary to systems of fusion of powers, the system of multiple separations of power functions without a government as the final locus of decision-making power. Such systems are proper unions of states rather than nation-states—in particular, unions of asymmetrically correlated states. Because of this (structural and cultural) asymmetry, such unions cannot accommodate the centralization of decision-making power. If institutions matter, then to classify the EU as a consensual democracy appears highly unconvincing. Like other democratic unions of states, such the United States and Switzerland, the EU is a species of a different democratic genus, and could be called a compound democracy. Asymmetrical unions of states can be subsumed neither under the model of consensual democracy nor under the models of majoritarian/competitive democracy, because they have neither a government nor an opposition. One might argue that they are Madisonian systems functioning on the basis of checks and balances between institutions and not between political options as in fusion-of-powers democracies. The classification of democratic patterns, if it is to take into consideration institutional systems, needs be enlarged to a more comprehensive typology. The development of the EU has allowed comparative politics to overcome national borders and apply its tools, concepts, methods, and theories to the study of a supranational political system. At the same time, the EU has also been compared with other regional organizations, a comparison that has shown the difference between political and economic regionalism. The comparative analysis of politics has been relaunched by the development of the EU.

Democratization and Consolidation

The end of the Cold War also had dramatic effects in the non-Western world, ushering in a new democratic era in Africa, Latin America, and Asia. In these regions, a process of democratization started with the aim of creating regimes able to provide, as it was claimed in many quarters, security in the sense of protection against widespread and arbitrary violations of civil liberties. Many political elites of new democratizing countries seemed to share the belief that a democratic regime has an intrinsic value. This belief was epitomized by the introduction of democratic rule in South Africa in 1994. On these empirical bases, the 1990s registered a diffusion of studies on democratization (e.g., Geddes, 2007), studies that benefitted largely from the previous generation of works on the democratization of Southern Europe and Latin America, such as that by Leonardo Morlino (1998).

Democratization has entailed the introduction of reforms aimed at limiting the role of the state in the political sphere. It has been about restoring political pluralism, whereby different political and civic organizations participate in the political process without hindrance. According to Ben O. Nwabueze (1993), democratization was meant to enhance transparency and accountability. Although most countries in Africa and Asia have introduced political changes in their polities, the crucial question, especially in Africa, has continued to be whether democratization is reversible or not. As Larry Diamond and Marc Plattner, among others, have pointed out, in some cases, newly established democratic orders have devolved into pseudodemocracies. Despite this, Africa, Asia, and Latin America have made tremendous progress toward democratization, although North Africa and the Middle East have yet to make a major step in this regard. Especially in the 1990s, scholars of comparative politics devoted their work to seeking to explain why some countries and not others were successful in transitioning from nondemocratic to democratic systems. Some studies focused on the strategic role played by individual leaders (Nelson Mandela in South Africa or Mahathir Mohamad in Malaysia) as key drivers of change and guarantors of political transformation. Others emphasized the role of specific institutional settings for supporting the democratization of a country. Still others have investigated the role of civil society in fostering or contrasting democratization, according to an approach not dissimilar to the social capital approach.

With the diffusion of democracy in Africa, Asia, and Latin America in the first decade of the 21st century, scholars have started to investigate the conditions that have helped or impeded the consolidation of democracy after two decades of repeated elections and broad institutional reforms. The challenges of democratic consolidation have been greater in Africa than in other parts of the world. The democratization of Eastern European and Latin American countries has been largely supported by regional organizations (e.g., as the EU or Mercosur [Mercado Común del Sur]). One of the conditions for participating in these organizations and for enjoying their economic benefits is that democratic principles should be respected. This has not been the case in Africa because of the fragility of the African Union. Although there are still cases of conflict and instability in countries such as Venezuela, Peru, Timor-Leste (East Timor), Thailand, Georgia, and Kyrgyzstan, these are isolated cases. It is in Africa that the consolidation of democracy has continued to be an open question. Although Africa has made a big step toward democratization, democracy is far from having been consolidated. Democratic reversal has continued to be a likely possibility for most African countries. The political crises in Kenya, Zimbabwe, and Madagascar in the past few years are cases in point. Democratic consolidation requires, among other things, a government turnover, and most countries in Africa are yet to undergo this crucial test. Even in countries that have maintained stability, such as Botswana and Namibia, one-party dominance remains a key feature of their democracy.

Quality of Democracy and Development

Following pioneering works on the quality of democracy, such as that by Larry Diamond and Leonardo Morlino (2005), scholars have investigated the same in the countries of Africa and Asia, reaching very critical conclusions. In Africa, due mainly to the low levels of development and widespread poverty, the traditional debate on democracy versus economic development has been very much alive (Adam Przeworski, Michael Alvarez, José Antonio Cheibub, & Fernando Limongi, 2000). In the 1990s, the return to multiparty democratic systems in African countries raised hopes and expectations for development. After almost two decades of multiparty elections, however, those hopes have begun to dwindle as development is slow and poverty levels have remained high. A number of surveys, such as those by the Afro Barometer Group, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), and Transparency International and several others based on regional and individual country comparisons, have been conducted in Africa on the subject of public perceptions of good governance, the effective delivery of services by the state, and levels of corruption and performance on human development indicators. In Asia, similar studies on public perceptions of democracy and the effects of government performance on development have been common.

Investigating developments in Africa and Asia, comparative politics scholars have come up with indicators that purport to measure democracy and good governance. The World Bank has been a leading institution in asserting that good governance is the basis for economic success. It has argued that those countries that have successfully instituted rule of law, established a culture of regular free and fair elections, and minimized corruption have been able to attract foreign private investors and thereby performed much better in development than those that have been unable to do so. Other organizations based mainly in Europe and North America, such as Freedom House, International Institute for Democracy, and the United Nations Development Program, have come up with criteria for assessing performance in political and civil rights, democracy, governance, and economic performance. In Africa, the UNECA has developed an elaborate survey methodology seeking to evaluate public perceptions of the state in various countries, comparing their performance on some key governance indicators, such as rule of law, freedom and fairness of elections, women's participation in politics, levels of corruption, and the effectiveness of the checks and balances between the core institutions of governance (with a particular focus on the independence of the judiciary).

Africa experienced poor governance and rampant corruption in the decolonization decades of the 1970s and 1980s, in part because of the diffuse corruption of public officials and governors. As a result, since the 1990s, Africa has been under pressure from international organizations and local reformers to embrace governance reforms. The African Union has acknowledged that good governance continues to be a challenge in Africa. It has therefore introduced the African Peer Review Mechanism and the African Union's Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption and Related Offences for improving the standards of governance in the continent. Finally, some investigations have shown a correlation between human development and political stability. Indeed, human development has evaded most countries of the developing world because political instability has continued to be a major and recurrent problem. Examples include Algeria, Burundi, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Africa; parts of India, Nepal, and Pakistan in Asia; and Colombia and Guatemala in Latin America.

Democracy and Constitutionalization

The study of constitutions and constitution-making processes features prominently in the comparative politics discourse, especially in the newly democratizing countries. The return to democratic rule has ushered in new debates on how best to craft and reform constitutions and helped ensure that constitutions facilitate democratic governance and protect human, ethnic, cultural, and other rights that characterize complex postcolonial and postconflict societies. In this regard, in Africa, the constitutions of Namibia and South Africa have been considered good examples because of their racial and ethnic balancing, power-sharing mechanisms, protection of basic human rights, and enshrined checks and balances. Constitutional reforms have been introduced in Kenya, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, and Lesotho to deal with internal conflicts. In these and other cases, the reform of the national constitution has been considered necessary for engineering peaceful political succession.

Many countries, especially in Africa, have set a two-term limit for the presidency. In practice, this innovative measure has sparked controversy and conflict in Malawi, Namibia, and Zambia, among others, where the outgoing president has sought to change the constitution to ensure that he could serve a third term. The third-term issue has thus become central in political debate. Succession is an area that has attracted interest and controversy in Africa and in some Latin American countries, such as Venezuela and Honduras. The succession not only to the state's presidency but also to the party leadership have become political issues. The cases of Botswana, Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, Nigeria, Uganda, South Africa, and Zimbabwe show that the African continent has not yet resolved these issues. Succession in the party has been a concern because it has been closely linked to succession in the presidency. As a result, political scientists such as Roger Southall and Henning Melber have focused on the role of former presidents, the legacies of political power, and the importance of term limits.

The issues of constitutions and constitution making have been central in the European debate also. Through the 1990s, all the Eastern European countries had to redefine their constitutional settings drastically. At the same time, the process of enlargement of the EU has accelerated the search for a new constitutional setting able to guarantee the functioning of a regional organization encompassing (in 2010) 27 member states and half a billion inhabitants. The first decade of the 21st century has been the constitutional decade of the EU, although this decade has witnessed the amendment of the existing treaties rather than the approval of a new and encompassing constitutional treaty. Even the contrasted process of constitutionalization of the EU has appeared less exceptional when compared with the experience of other compound democracies. This debate has also led to a vivid discussion on European citizenship and more generally on how to guarantee human rights in a multilevel supranational system.

Democracy and Representation

Political representation has changed dramatically since the end of the Cold War. In established democratic systems, starting with the United States, political parties have entered a long phase of downsizing and restructuring. Mass political parties have become icons of the past. Political parties have become state agencies in Europe (as argued by Richard Katz and Peter Mair) and electoral committees in the United States (as argued by Sandy Maisel). On both sides of the Atlantic, they have developed as supporting structures of the leader at the electoral and governmental level. A vast literature has shown how parties have been integrated by other actors in the electoral arena. While in the West scholars have been investigating the consequences on governance of the decline and transformation of political parties, in the non-Western world, the research issue has been the opposite: What role can newly founded parties play in promoting democracy? In democratizing countries, strong political parties have been considered a necessary pillar for supporting democratic consolidation (M. A. Mohamed Salih, 2003). Political parties have generally been weak and constrained by a lack of resources. This has also drawn attention to the issue of their funding. The weakness of political parties has been fed also by their tendency to fragment along ethnic lines or to rally around a founder patron who has often constrained their ability to institutionalize and practice internal democracy. Opposition parties, in particular, have been conflict ridden and fragmented throughout the new democracies, leading to their poor showing at elections.

In Africa, Asia, and Latin America, comparative politics has focused, in particular, on the functioning of elections, thus contributing to identify criteria for evaluating the legitimacy of the electoral process. The issues have concerned the impact of election rules on the legitimacy of emerging democracies, the institutional conditions that make elections free and fair, the role of electoral management bodies as institutions of governance, and the implications of observation and monitoring on the outcome of the electoral process. These studies have inspired specific regulations, such as the Southern African Development Community's (SADC) Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections and the Electoral Institute of Southern Africa/Electoral Commissions Forum's Principles for Election Management, Monitoring and Observation in the SADC Region, both made public in 2004. That notwithstanding, in many African countries, elections have not called into question the power of former liberation movements or ruling parties to dominate domestic politics.

Weakened parties in the European parliamentary democracies have contributed to the decision-making decline of legislatures, thus leaving larger room for maneuvering to the executives. Indeed, parties have come to be controlled by their leader once in government, thus justifying, as noted by Thomas Poguntke and Paul Webb, a process of presidentialization of politics in modern democracies. This process has not concerned separation of powers systems; the U.S. Congress has continued to be the most powerful legislature in the democratic world. Although for different reasons, in non-Western democracies also, parliaments have continued to remain weak institutions. For instance, it has been argued that African parliaments have been weak because of both one-party dominance of the country and an overly powerful executive, although other studies have pointed to a lack of public support for them.

To foster such support, proposals for integrating traditional institutions of leadership and governance into modern structures of representation were advanced. These traditional institutions are still influential at local and regional levels in many countries around the world. In Africa, the institution of chieftaincy, or even kingdom, is still important in people's daily existence. Political efforts to sideline, and in some countries to abolish, these traditional institutions have not succeeded. Many countries, in Africa especially, have molded their modern governance institutions around traditional ones. Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa present a model that seems to have struck a balance of mutual respect between modern and traditional institutions. In other countries such as Zimbabwe, chiefs have been directly co-opted into parliament, while in other countries such as Swaziland, it has been the traditional monarchy that has sought to incorporate modern political institutions.

The return to institutional approach in comparative politics is linked to global support for democracy. Many development agencies (e.g., as the U.S. Agency for International Development, the United Nations Development Programme, and other nongovernmental organizations) have devoted significant resources to the strengthening of the institutions of governance. In particular, across the former Soviet Union, Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the focus has been on strengthening parliamentary and judiciary institutions, and academics and practitioners are studying these programs to assess their impact. A substantial body of comparative politics literature on development assistance has thus emerged.

Comparative Policy Analysis

The interest in the organization and functioning of democratic regimes has inevitably promoted research on the latter's performance by scholars of comparative politics. Starting with the 1981 volume edited by Peter Flora and Arnold J. Heidenheimer during the 1980s, the comparative approach to policy analysis came to be adopted by many scholars, in particular for understanding the historical development of different welfare systems and for explaining the different features of welfare policies in Western Europe and the United States, as shown by the contributions of Gøsta Esping-Andersen, Paul Pierson, and Francis Castles. One might argue that the analysis of Western welfare policies constitutes the starting point of comparative policy analysis, and even today, it represents its core business.

However, with the end of the Cold War and the development of the globalization process, the comparative study of welfare systems has come to include the analysis of new social risks, risks that epitomize the pathology of contemporary postindustrial societies, as argued in the volume edited by Peter Taylor-Gooby in 2004. At the same time, the diffusion of the process of globalization has made the Western experience with welfare systems less peculiar than in the past. The problems associated with guaranteeing social security in market societies have come to be shared by many countries—developing as well as developed, democratizing as well as democratic. Market globalization has generated new social externalities, bringing to the center of comparative policy analysis new problems, such as immigration and environmental issues. In this regard, one has to consider the 1997 volume edited by Martin Janicke, Helmut Widner, and Helge Jorgens on national environmental policies and the 2007 volume by Eytan Meyers on international immigration policy.

Starting in the 1990s, the field of public policy has also seen a dramatic expansion. Globalization and Europeanization have not only created new problems, but they have pressured international institutions to promote thorough investigations of the economic, financial, administrative, and political performance of the various countries, investigations accompanied by frequent, specific recommendations for public policy. The conspicuous development of comparative policy analysis has been made possible by an easier access to empirical data concerning the various members of international and regional organizations. The latter have also supported specific policy priorities, introducing new criteria for evaluating countries' approximation to the expectations for good governance, including the call for the promotion of gender equality. Indeed, since the second half of the 1990s, gender policy has emerged as a significant policy interest, and not just in developed countries, as shown by the 1995 volume edited by Dorothy McBride Stetson and Amy G. Mazur. This policy field has been finalized not only to investigate the structural constraints on women's participation in the economic and social life of a country but also to identify resources and practices that might promote women's interests in the various national contexts.

The gender approach to public policies has thus called into question the normative premises of many public policies. In fact, the latter have been based on a culturally defined view of family organization, social needs, and individual expectations. The same concept of security has been redefined to meet new social preferences and personal attitudes. Indeed, the comparative study of public policy has led to a greater understanding of the value structures of contemporary societies, thereby helping combine empirical analysis and normative assessments.

The Future of Comparative Politics

Comparative politics (as an academic discipline) has been a major success. In the post–Cold War era, our knowledge of democratic, democratizing, and nondemocratic political systems has grown enormously. The methodologies, concepts, and theories of comparative research are widely used by political scientists. With the exception of the United States, where "American politics" scholars constitute the majority, comparative politics has become the central subdiscipline of world political science. Indeed, as noted by Henry Brady and David Collier, the discipline as a whole has been defined epistemologically by the debate in comparative politics. However, the success story of comparative politics has reached a critical juncture. Comparative politics is encountering issues with confronting the political problems of a globalized world. Its methods and theories face difficulties when applied to processes that transcend state borders and undermine the structure of the traditional political relations on which comparative politics is based.

The historical transformations that have occurred after the end of the Cold War have called into question the concept of sovereignty itself, which is the foundation of the study of comparative politics. With the processes of globalization that have unfolded tempestuously since then, the external and internal sovereignty of the nation-state (the basic unit of analysis of comparative research) has been eroded. Simultaneously, the complexity of political systems and their external relations has increased to such an unprecedented extent as to give rise to a complex interdependence. This complex interdependence is changing the nature, powers, and outlook of the units used by comparative analysis for the study of politics. It simultaneously disarticulates domestic and international politics, creating more levels of correlation between variables, levels that are not necessarily connected with each other.

This being so, it becomes increasingly less plausible to establish what constitutes an independent cause of a dependent outcome. If domestic political systems are not independent of external processes and if the actors that operate within them do not have the ability to act as agents that connect cause and effect, then the fundamental preconditions of comparative analysis are being eroded. Therefore, it is increasingly less likely to assume that the various political systems are distinct entities, because in reality, they are not.

Globalization and Europeanization

Domestic political systems are embedded in an institutionalized international context that noticeably constrains the autonomy of their decisions. The majority of nation-states are members of international economic organizations (e.g., the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization) or of military alliances (e.g., the North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO] and South East Asia Treaty Organization [SEATO]) where decisions are made (with their participation, of course) that have significant domestic implications. Over and above this, the sovereignty of the nation-state is also being eroded from below. At least in Europe, the unitary and centralized state is being superseded. New regional and municipal authorities have emerged and have become institutionalized. Not only has the room for maneuver of the national or central authorities been reduced, but the cognitive context itself, within which their actions unfold, has changed. Our conception of the state has been modified.

Globalization, as noted by Philippe Schmitter, has become the independent variable in many national contexts. It has reduced the impermeability of the nation-states to external pressures. This, in turn, has weakened relations between the citizens and the institutions of those states, as soon as the former have become aware that the latter are unable to respond to their demands. The legitimacy of public institutions has been further reduced by the growing role that noninstitutional actors have acquired in the context of globalization. These actors comprise companies, associations, and transnational nongovernmental organizations that operate outside the border of single states, and they have contributed to the emergence of new supranational regulative systems or international regimes. One may claim that no nation-state (not even the most important ones like the United States or China) is able to control domestic decision-making processes, autonomously steer its own economic dynamics, or develop its own separate cultural identity.

If globalization has challenged the assumptions of comparative politics, this is even truer in the case of the Europeanization induced by the process of European integration. There are many definitions of Europeanization. According to Vivien Schmidt, it consists in the process through which the political and economic dynamics of the EU have become part of the institutional and cultural logic of domestic politics. However, one defines Europeanization, there can be no doubt that it consists of the implementation, at the level of the single member states, of institutional procedures, public policies, and cognitive frameworks to address the domestic problems deriving from the EU level. No member state of the EU (not even those most proud of their own traditional sovereignty, e.g., the United Kingdom and France, or those most proud to have recently regained sovereignty, e.g., Poland and the Czech Republic) can decide (in myriad areas of public policy) on the basis of autonomous considerations. This does not mean that the European nation-states have disappeared. Rather, it is even plausible to argue, as Alan Milward has done, that European integration has rescued them, taking care of tasks they were no longer able to tackle. This, however, means that their sovereignty has been eroded and redefined. They are sovereign in some areas of public policy (e.g., defense and, partially, foreign affairs), whereas they are entirely bereft of sovereignty in other areas (e.g., monetary policy and, more generally, all areas related to the creation of the common market). In yet other areas (e.g., environmental and research policies), they share sovereignty.

It is clear that Europeanization constitutes a formidable challenge to the assumptions of comparative politics—namely, to conceive of the European states as sovereign and independent units that are autonomous in terms of decision making. In Europe and elsewhere, the dividing line between internal (domestic) politics and external (international) politics has shifted significantly (Robert Elgie, 1999).

Toward an International Comparative Politics

Globalization and Europeanization have brought radical transformations to the states and to the relations between them. These transformations call into question the traditional distinction between comparative politics and international relations. Regarding comparative politics, the sovereignty of nation-states has been fundamentally questioned. Sovereignty has been unpacked, fragmented, and segmented, thereby challenging a long normative (and hypocritical) tradition that assumed that sovereignty is an indivisible reality. The same supposed order of the domestic polity is dramatically belied by the fact that most of the major conflicts that occurred during the 1990s have happened within states rather than between them. Regarding international relations, it is no longer certain that the international system is the anarchic world that has formed the basic condition of interstate relations. This system is organized in several international regimes and managed by several international organizations, each of them equipped with tools and norms to peacefully adjudicate disputes between public and private actors.

Various studies have recognized that the epistemological and methodological boundaries between the two subdisciplines of political science are no longer evident. Scholars developing the foreign policy analysis approach have included the domestic structure of a given regime in their analysis, showing how it exerts a significant influence on the decisions and styles of foreign policy of a country. Scholars investigating the relations between the economic structures and the political arrangements of various countries have shown the interactions between international pressures and domestic arrangements (with their effects on the organization of markets, the construction of welfare regimes, the organization of systems of representation, and interest intermediation). One could mention the most recent literature on democratic peace, which has sought to show why democratic countries do not go to war with each other, because of the domestic constraints to which their decision makers are subjected; however, this does not imply that they are not inclined to go to war with nondemocratic countries. Finally, leading international relations scholars have continued to work with models connecting international and domestic variables.

These and other studies have called for the development of an integrated political science that is subdivided by the topics it seeks to study rather than by the units of analysis chosen (the domestic system or the international system). A political world marked by complex interdependence calls for a political science ready to experiment with new methods and new theories. A new field of study, which some scholars call International Comparative Politics, might be developed to confront the challenges of this world. However, the structure of academic careers, still rigidly organized around the distinction between the two subdisciplines, will make such development difficult.

Conclusion

The fundamental transformations induced by the processes of globalization and Europeanization have ended up questioning the methodological and theoretical self-sufficiency of comparative politics. These processes have urged scholars of comparative politics to take the international context of a country into account as an essential variable in explanations of the functioning of domestic politics. Simultaneously, the effects of domestic structures on supranational and international processes have driven international relations scholars to reexamine the methodological and theoretical self-sufficiency of their discipline. Substantial changes in the real world of politics are urging political scientists to develop methods and theories that can come to terms with the complex domestic and international forces that shape the important problems requiring study and explanation. After all, the undertaking of political science, as of all other social sciences, is justified by its ability to furnish plausible solutions to real problems. Accordingly, the profession should not be afraid to question itself, to overcome consolidated divisions between subdisciplines, and to seek new perspectives. A self-sufficient political science serves neither political scientists themselves nor the citizens of the contemporary world.

References:

- Boix, C., & Stokes, S. (Eds.). (2007). The Oxford handbook of comparative politics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Brady, H. E., & Collier, D. (Eds.). (2004). Rethinking social inquiry: Diverse tools, shared standards. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Cain, B. E., Dalton, R. J., & Scarrow, S. E. (Eds.). (2004). Democracy transformed? Expanding political opportunities in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Caramani, D. (Ed.). (2008). Comparative politics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Della Porta, D., & Keating, M. (Eds.). (2008). Approaches and methodologies in the social sciences: A pluralist perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Diamond, L., & Morlino, L. (Eds.). (2005). Assessing the quality of democracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Elgie, R. (Ed.). (1999). Semi-presidentialism in Europe: Comparative European politics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Fabbrini, S. (2008). Politica comparata: Introduzione alle democrazie contemporanee [Comparative politics: Introduction to contemporary democracy]. Roma-Bari, Italy: Laterza.

- Fabbrini, S. (2010). Compound democracies: Why the United States and Europe are becoming similar (2nd rev. ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Flora, P., & Heidenheimer, A. J. (Eds.). (1981). The development of welfare states in Europe and America. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Geddes, B. (2007). What causes democratization? In C. Boix & S. Stokes (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative politics (pp. 317–339). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Hall, P. A., & Taylor, R. C. R. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44(5), 936–957.

- Katznelson, I., & Milner, H. V. (Eds.). (2002). Political science: State of the discipline. New York: W. W. Norton.

- King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994).

- Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Lijphart, A. (1999). Patterns of democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1989). Rediscovering institutions: The organizational bases of politics. New York: Free Press.

- Morlino, L. (1998). Democracy between consolidation and crisis: Parties, groups, and citizens in Southern Europe. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Nwabueze, B. O. (1993). Democratization. Ibadan, Nigeria: Spectrum Law.

- Poguntke, T., & Webb, P. (Eds.). (2007). The presidentialization of politics: A comparative study of modern democracies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M. E., Cheibub, J. A., & Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and development: Political institutions and well-being in the world, 1950–1990. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic tradition in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ragin, C. (1994). Constructing social research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

- Salih, M. A. (Ed.). (2003). African political parties. London: Pluto Press.

- Sartori, G. (2009). Concept misformation in comparative politics. In D. Collier & J. Gerring (Eds.), Concepts and method in social science: The tradition of Giovanni Sartori (pp. 13–43). London: Routledge. (Original work published 1970, American Political Science Review, 64, 1033–1041)

- Schmitter, P. (2009). The change and future of comparative politics. European Political Science Review, 1(1), 33–61.

- Southall, R., & Melber, H. (Eds.). (2005). Legacies of power: Leadership change and former presidents in African politics. Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press.

- Stetson, D., & Mazur, A. (Eds.). (1995). Comparative state feminism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cases in Comparative Politics 5th Edition Chapter Summaries

Source: https://political-science.iresearchnet.com/comparative-politics/